In this article, I will guide you through the process of setting up a rootless container host using containerd . We will use nerdctl (a Docker-compatible CLI) to interact with the container runtime. I will also explain how User Namespaces enable a non-root user account to run containers as different users and how to setup host volumes with the correct permissions for those users. Finally, I will configure an IP whitelist using iptables and ipset to ensure that services are only reachable from the IP addresses that we allow.

This article is targeted at people who want to set up a (private) rootless container host using containerd instead of Docker or people who are just interested in reading about this use-case. It is not intended for beginners. If you’re new to containers, tools like Docker or Podman are probably a better starting point. For this article, I will assume that you are somewhat comfortable with the command-line and that you know how to log in to a Linux server via SSH or the console.

Why Containerd?

To be completely honest, the main reason I chose to use containerd instead of Docker or Podman, is to learn new things and experiment. It seemed like fun and challenging topic.

That said, there are some reasons why you might actually want to do this:

- Containerd is the default container runtime for Kubernetes

- Containerd is OCI compliant and CRI compliant

- Containerd is more lightweight and more performant than Docker

- You want to develop an application or interface that uses the CRI specification

- You want to run a single node with a standalone Kubelet for development

- You want to experiment and interact with containerd directly to become more familiar with the technology and how to troubleshoot it

While containerd is more performant, it is less user friendly and requires more work to setup. We can solve the ease of use issue by using nerdctl and we can automate the server setup and container deployments using Ansible . For this article however, we will be setting up our server manually.

On our local machine, we can still use Docker to develop, build and test images. Docker builds produce OCI compliant container images which containerd can use without issue.

Limitations

Unfortunately, at the time of writing this article, remote management of containerd is not that simple. I searched for solutions such as running a standalone kubelet , using nerdctld , exposing the containerd socket over the network with SSH or TCP using tools like socat and stunnel and using ctr directly.

Due to their complexity, none of these solutions seemed appealing to me so, I decided to just use nerdctl on the target machine for now. We can still automate that part using Ansible later on and if I find a better solution in the future, I will surely write an article about it.

Server Setup

I will be using ubuntu 24.04 LTS server as the operating system. For convenience, I will be using a Digital Ocean droplet while writing this article. You can use my referral link to get some free credit and get started. I like Digital Ocean because it is fast, cheap and you can top up your account without the need for a credit card. The droplets spin up in under a minute and have a fast internet connection which makes downloading and installing packages a breeze.

The instructions in this article should work on any virtual machine or bare-metal server with Ubuntu 24.04 installed but, for the article I used x86 hardware and I have not tested it on other architectures. You might need to install different binaries of the CNI Plugins and Nerdctl for your architecture.

I will not be covering the installation of Ubuntu itself here (You can have a look at my post Creating a Professional Home Lab Setup Part 1 - Installing the Operating System on Medium for instructions on how to do that).

Installing Containerd and the CNI

After we have installed the operating system (or created the droplet), we can log in to the server using the system console or SSH.

Note

If you are using a Digital Ocean droplet, you will need to login as root.

Let’s start by updating the server and installing rootlesskit , containerd and slirp4netns :

# update system packages

sudo apt update && sudo apt -y upgrade

# install rootless containerd requirements

sudo apt -y install rootlesskit slirp4netns containerd

If there was a kernel update, it is a good idea to reboot the machine:

# only needed if there was a kernel update

sudo reboot

The containerd runtime does not come with the CNI

plugins installed. We will need to install them separately.

The CNI plugins will be installed in /opt/cni/bin/:

# change this to the latest release on https://github.com/containernetworking/plugins/releases

CNI_PLUGINS_VERSION=1.6.2

# check the cni releases page for available architectures

ARCHITECTURE=amd64

curl -LO https://github.com/containernetworking/plugins/releases/download/v${CNI_PLUGINS_VERSION}/cni-plugins-linux-${ARCHITECTURE}-v${CNI_PLUGINS_VERSION}.tgz

sudo mkdir -p /opt/cni/bin

sudo tar -C /opt/cni/bin -xvzf cni-plugins-linux-${ARCHITECTURE}-v${CNI_PLUGINS_VERSION}.tgz

While we are at it, we will also install nerdctl. It will be installed in /usr/local/bin:

Note

nerdctl includes scripts that facilitate installing and running a rootless containerd. If you want to know how this is works, take a look at the nerdctl documentation .

# change this to the latest release on https://github.com/containerd/nerdctl/releases/

NERDCTL_VERSION=2.0.3

# check the nerdctl releases page for available architectures

ARCHITECTURE=amd64

curl -LO https://github.com/containerd/nerdctl/releases/download/v${NERDCTL_VERSION}/nerdctl-2.0.3-linux-${ARCHITECTURE}.tar.gz

sudo tar -C /usr/local/bin/ -xvzf nerdctl-${NERDCTL_VERSION}-linux-${ARCHITECTURE}.tar.gz

After installing the required the packages and tools, the first thing we need to do is stop and disable the rootful containerd service that was automatically enabled while installing containerd:

# disable and stop containerd service

sudo systemctl disable --now containerd

We also need to make sure that rootlesskit is allowed to bind reserved well-known ports . You can find more information about that here .

sudo setcap cap_net_bind_service=ep /usr/bin/rootlesskit

Now, we can create an unprivileged user account that will be used to run containerd:

# we don't want this user to be able to login because it is a system account

# (change the user home directory in the command below to wherever you want to store your containerd data)

sudo useradd containerd -d /home/containerd -m -s /usr/sbin/nologin

We will also need to enable lingering for this user account:

Note

From the man page:

enable-linger [USER...], disable-linger [USER...]

Enable/disable user lingering for one or more users. If enabled for a specific

user, a user manager is spawned for the user at boot and kept around after

logouts. This allows users who are not logged in to run long-running services.

Takes one or more user names or numeric UIDs as argument. If no argument is

specified, enables/disables lingering for the user of the session of the

caller.

# this does not require a reboot

sudo loginctl enable-linger containerd

Finally, we will install and run the rootless containerd service as the containerd user:

Note

We need to use sudo to spawn a bash shell in this way because the containerd user is not allowed to log in.

# XDG_RUNTIME_DIR is required for systemd and is normally set during login

sudo -u containerd bash -c 'export XDG_RUNTIME_DIR=/run/user/${UID}; cd; bash'

# this will check some prerequisites and create and start the rootless containerd service

# this script was installed with nerdctl in /usr/local/bin

containerd-rootless-setuptool.sh install

Check the installation output for any errors (You can ignore the CRI Service error).

Note

From this point on it will be useful to keep two separate terminals open. One logged in as the sudo user (or root) and another one for containerd. That way it will be easy to run sudo commands in the sudo user (or root) shell while using the containerd user shell to run nerdctl and systemctl commands.

Testing the Waters

With nerdctl, containerd and the CNI installed, it is time to test the waters by running some (rootless) containers:

nerdctl run -ti --rm alpine:latest -- id

The output of the command above will show that the latest alpine image is pulled from the registry and that the user inside of the container is root.

We can test if we have root privileges on the host system by mounting the root filesystem as a volume and trying to read a protected file:

nerdctl run -v /:/rootdir -ti --rm alpine:latest -- cat /rootdir/etc/shadow

This command will output: cat: can't open '/rootdir/etc/shadow': Permission denied.

That is exactly what we want. Even though we are root inside of the container, we do not have root privileges on the host system. We can see exactly what is going on if we use a container to create a file in a mounted volume:

# create an empty file in the containerd home directory

nerdctl run -v ${HOME}:/homedir/ -ti --rm alpine:latest -- touch /homedir/test.txt

# list the file that was just created outside of the container

ls -l

# -rw-r--r-- 1 containerd containerd 0 Feb 27 22:14 test.txt

# list the file that was just created inside of the container

nerdctl run -v ${HOME}:/homedir/ -ti --rm alpine:latest -- ls -l /homedir/

# -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Feb 27 22:14 test.txt

We can see that the root user inside the container is actually mapped to the containerd user on the host system.

As a final test, we can start an nginx web server and publish port 80 on the host system:

# this will output a unique container ID and start the nginx container in the background

nerdctl run -d -p 80:80 --name nginx nginx:latest

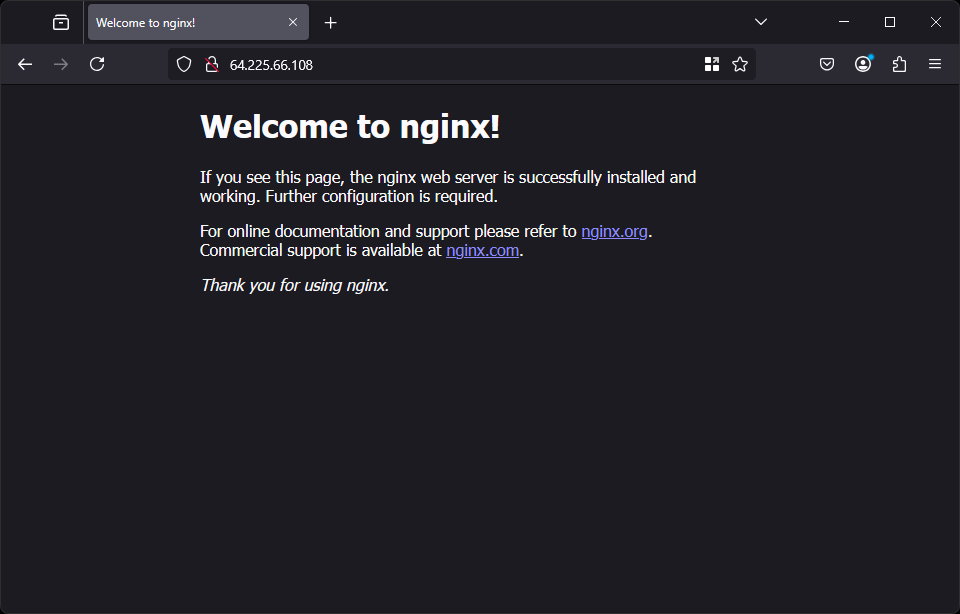

If we open a browser and navigate to the server’s IP address (In my case 64.225.66.108),

we will see the nginx welcome page, confirming that our rootless container is running and is published on port 80.

When we have finished proudly staring at our rootless containerized service, we can list and clean up the nginx container with the following commands:

# list running containers

nerdctl ps

# stops and removes the container

nerdctl rm -f nginx

User Namespaces and ID Mappings

You might ask yourself: “What happens if I try to use a non-root user account inside of a container?” and that would be an excellent question! We can try it by running an ubuntu 24.04 container that has a user account called ubuntu built-in.

nerdctl run --name ubuntu --user ubuntu -ti --rm ubuntu:24.04 -- id

This works as expected and will output the information of the ubuntu user.

We can see that the user id and group id of the ubuntu user within the container are 1000:

uid=1000(ubuntu) gid=1000(ubuntu) groups=1000(ubuntu),4(adm),20(dialout),...

Now, let’s try to use this containter to create a file in our home directory:

nerdctl run --name ubuntu --user ubuntu -ti --rm \

-v ${HOME}:/homedir ubuntu:24.04 -- touch /homedir/test-non-root.txt

Running this command will lead to the following error message:

touch: cannot touch '/homedir/test-non-root.txt': Permission denied

What happened here? If we run the id command outside of the container,

we can see that our containerd user is also using a user id and group id of 1000:

uid=1000(containerd) gid=1000(containerd) groups=1000(containerd)

That is where User Namespaces come in. It allows a non-root user to map user and group ids on the host system to a different range of user and group ids within the namespace. The ubuntu user within the container is mapped to a predefined range of ids on the host system. You can find the configuration of these ranges in the following files:

# /etc/subuid

containerd:100000:65536

# /etc/subgid

containerd:100000:65536

This means that the containerd user account is allowed to map user and group ids from 100000 up to and including 165535.

The mapped ids inside of containers are calculated as an offset from the start of the range.

However, since root (uid 0) is mapped to the containerd user (uid 1000) on the host, the mapping starts from uid 1.

This means that the user ubuntu with the uid of 1000 inside of the container is mapped to the uid of 100999 on the host.

Tip

If this offset irritates you, simply modify the start of the range in the configuration files mentioned above to 100001.

Keep in mind that if you change this, you will also need to restart the containerd service with the following command:

# run this as the containerd user

systemctl --user restart containerd

For the purpose of this article, we will leave the settings at the default.

Then how can we mount host volumes for our containers? The solution is to create the volumes for our containers in advance and change the ownership to the ids mapped on the host:

Note

We have to run the commands below as a user that is allowed to run sudo (or as root) because the containerd user is not allowed to change ownership to the mapped ids. I understand that this whole process is quite painful and that is why deployments like these should most definitely be automated.

# change this to the home directory path of the containerd user

CONTAINERD_HOMEDIR=/home/containerd

# create the volumes directory owned by containerd

sudo install -d ${CONTAINERD_HOMEDIR}/volumes -o containerd -g containerd

# create the ubuntu volume with owner 100999 and group 100999

sudo install -d ${CONTAINERD_HOMEDIR}/volumes/ubuntu -o 100999 -g 100999

After we have created the volume directories, the ubuntu user can read and write in this directory:

# create an empty file in the data volume

nerdctl run --name ubuntu --user ubuntu -ti --rm \

-v ${HOME}/volumes/ubuntu:/data ubuntu:24.04 -- touch /data/test-non-root.txt

# list the data directory contents

nerdctl run --name ubuntu --user ubuntu -ti --rm \

-v ${HOME}/volumes/ubuntu:/data ubuntu:24.04 -- ls -l /data/

# list the data directory contents outside of the container

ls -l ${HOME}/volumes/ubuntu

You will notice that the new file test-non-root.txt is owned by the ubuntu user within the container

and that it is owned by the user 100999 outside of the container.

Exploring the Configuration

Note

The file trees below are created using the tree command.

We did not install this command in this article because it is

just used for demonstration purposes.

If you want to install it yourself, you can use the following command:

sudo apt -y install tree

Now that we have started a few containers and understand how everything works, let’s have a look at what actually happened under the hood.

While running the commands in this article, the .config directory in the containerd user’s home directory

was populated with the following files:

tree ~/.config

.config/

├── cni

│ └── net.d

│ ├── default

│ └── nerdctl-bridge.conflist

├── containerd

└── systemd

└── user

├── containerd.service

└── default.target.wants

└── containerd.service -> /home/containerd/.config/systemd/user/containerd.service

8 directories, 3 files

- The

systemdfolder contains the user systemd service that was created during the installation of the rootless containerd - The

containerdfolder remains empty since we do not have any custom configuration for containerd - The

cnifolder contains network configuration for the CNI. It has the default network and a bridge network that was automatically created by nerdctl while running our containers.

On top of that the .local directory has was also populated with files needed to run our containers.

It contains the storage for containerd and includes things such as container image layers, container volumes, the overlayfs and snapshots.

# we limit the level to 5 to avoid printing the container overlayfs directories

tree -L 5 ~/.local

containerd@ackerspace:~$ tree -L 5 .local/

.local/

└── share

├── cni

│ ├── networks

│ │ └── bridge

│ │ ├── last_reserved_ip.0

│ │ └── lock

│ └── results

├── containerd

│ ├── io.containerd.content.v1.content

│ │ ├── blobs

│ │ │ └── sha256

│ │ └── ingest

│ ├── io.containerd.metadata.v1.bolt

│ │ └── meta.db

│ ├── io.containerd.runtime.v1.linux

│ ├── io.containerd.runtime.v2.task

│ │ └── default

│ ├── io.containerd.snapshotter.v1.blockfile

│ ├── io.containerd.snapshotter.v1.btrfs

│ ├── io.containerd.snapshotter.v1.native

│ │ └── snapshots

│ ├── io.containerd.snapshotter.v1.overlayfs

│ │ ├── metadata.db

│ │ └── snapshots

│ │ ├── 1

│ │ ├── 10

│ │ ├── 11

│ │ ├── 12

│ │ ├── 13

│ │ ├── 14

│ │ ├── 15

│ │ └── 16

│ └── tmpmounts

└── nerdctl

└── 1935db59

├── containers

│ └── default

├── default

├── etchosts

│ └── default

└── volumes

└── default

Limiting Network Access

Info

For this article I keep the iptables rules to the bare minimum to keep things simple. You will most likely want to customize these rules later and also add ipv6 rules which I have completely omitted here. If you want you can even create specific whitelists per port on the server or per destination network.

You may have noticed that, when we ran the nginx container, we immediately had access to port 80 without specifying our IP address anywhere. This is because our rootless containerd cannot manage iptables rules on the machine. In fact, even if it did, by default, containers would still publish ports worldwide. If we want to restrict access to our containers, we will have to configure iptables with an IP whitelist.

We will start by installing the tools required to facilitate this:

Info

This will disable ufw (Uncomplicated Firewall) if it was enabled

sudo apt -y install iptables ipset iptables-persistent ipset-persistent

- The package

ipsetmakes it easy to create sets of IPs to use with iptables - The package

iptables-persistentpersists changes to iptables after a reboot - The package

ipset-persistentpersists changes to ipsets after a reboot

Next let’s create a new empty IP set called whitelist:

# create an ip set consisting of hash of network cidrs

sudo ipset create whitelist hash:net

# list ip sets

sudo ipset list

If we list the current iptables rules, we will see that every policy is set to ACCEPT and access to the server is allowed without restrictions:

sudo iptables -L

Chain INPUT (policy ACCEPT)

target prot opt source destination

Chain FORWARD (policy ACCEPT)

target prot opt source destination

Chain OUTPUT (policy ACCEPT)

target prot opt source destination

Let’s first add some rules to make sure or server continues to work properly:

# always allow local (loopback) traffic

sudo iptables -A INPUT -i lo -j ACCEPT

sudo iptables -A OUTPUT -o lo -j ACCEPT

# Allow SSH from anywhere

# be careful not to lock yourself out if you restrict this further

sudo iptables -A INPUT -p tcp -m tcp --dport 22 -j ACCEPT

# Allow inbound and forward connections from our IP whitelist

sudo iptables -A INPUT -m set --match-set whitelist src -j ACCEPT

sudo iptables -A FORWARD -m set --match-set whitelist src -j ACCEPT

Next, we can change the default policy for the INPUT and FORWARD chains to DROP.

sudo iptables -P INPUT DROP

sudo iptables -P FORWARD DROP

This will block any inbound or forwarded connections outside of our whitelist (which, for the moment is empty). SSH is still always allowed.

Note

The IP set and firewall rules have been applied but have not yet been made them persistent by using the iptables-save command. If you lock yourself out of the machine, simply rebooting it will restore the state to where we started. You can also use the command iptables -F <CHAIN> to flush the chain rules and start over. For example:

# change chain the policies back to accept

sudo iptables -P INPUT ACCEPT

sudo iptables -P FORWARD ACCEPT

# flush the chains

sudo iptables -F INPUT

sudo iptables -F FORWARD

sudo iptables -F OUTPUT

We can now once again start the nginx container and bind it to port 80 on the server:

# this will output a unique container ID and start the nginx container in the background

# we will also use the restart policy to automatically start the container after a reboot

nerdctl run -d -p 80:80 --name nginx --restart unless-stopped nginx:latest

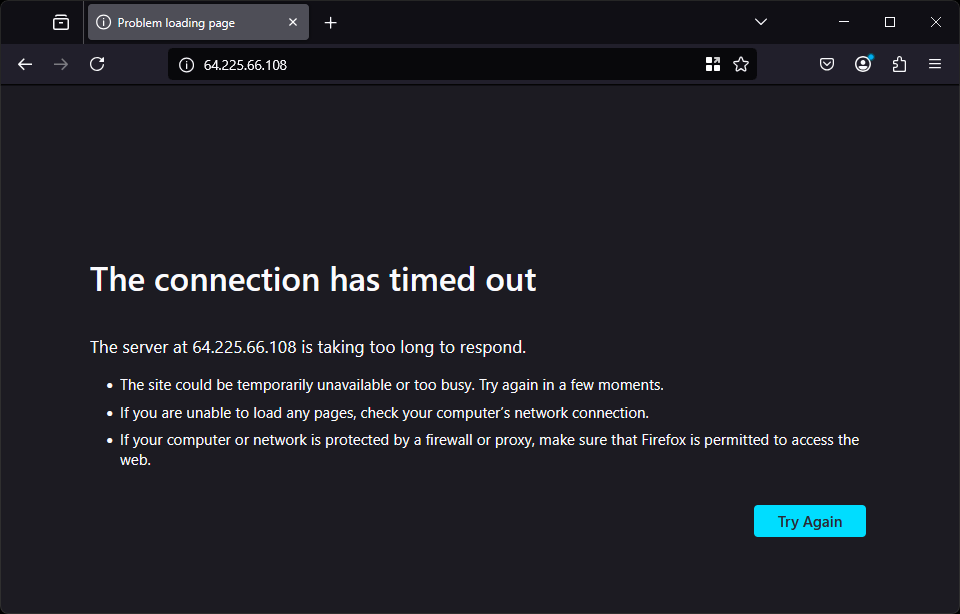

If we open a browser and navigate to the IP address of our server, we can see that the connection times out because the iptables firewall is blocking us:

When we add our own IP address to the IP set, we will have access to the nginx server:

# change the entry of 1.2.3.4 below to your ip address

# * you can find your ip address by browsing to https://httpbin.org/ip

# * you can enter a single ip address or a CIDR block

sudo ipset add whitelist 1.2.3.4

If we are happy with the results, we can use iptables-save to make our changes persist.

sudo iptables-save | sudo tee /etc/iptables/rules.v4

sudo ipset save | sudo tee /etc/iptables/ipsets

After a reboot of the server, you will notice that all of the iptables rules and ip sets have been restored.

Tip

If you are running a rootful containerd service that is managing iptables rules you can still add an ip whitelist by using the contidtionsV4 and conditionsV6 directives in your cni configuration files at /etc/cni/net.d/ as described here

.

For example:

{

"type": "portmap",

"capabilities": {

"portMappings": true

},

"conditionsV4": ["-m", "set", "--match-set", "whitelist", "src"],

"conditionsV6": []

},

Tip

You can use the following commands to manage your IP sets:

# create a new ip set

sudo ipset create SETNAME

# add an entry to the ip set

sudo ipset add SETNAME ENTRY

# remove and entry from the ip set

sudo ipset del SETNAME ENTRY

# remove the ipset

sudo ipset destroy SETNAME

What’s Next?

I hope you have enjoyed yourself and have learned something from this article. In the future, I plan to write some more articles detailing how to automate this setup with Ansible, how to use nerdctl compose to deploy containers and how to properly manage and monitor these container deployments. I also want to take a look at bypass4netns to improve the network performance of namespaced networking.

Ariticle Discussion and Comments

I have not integrated a commenting system on the website, instead you can comment on this acrticle in the following Github Discussion .

Sources

- https://access.redhat.com/articles/5946151

- https://github.com/containerd/containerd/blob/main/docs/getting-started.md

- https://github.com/containerd/containerd/blob/main/docs/rootless.md

- https://github.com/containerd/nerdctl/blob/main/docs/rootless.md

- https://github.com/rootless-containers/rootlesskit/blob/v0.14.1/docs/port.md#exposing-privileged-ports

- https://github.com/rootless-containers/slirp4netns

- https://ipset.netfilter.org/

- https://rootlesscontaine.rs/getting-started/common/login/

- https://wiki.qemu.org/Documentation/Networking

- https://www.cni.dev/plugins/current/meta/portmap/